Naimans

ᠨᠠᠶᠢᠮᠠᠨ | |

|---|---|

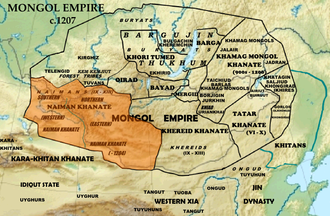

Location of the Naiman khanate at the start of the Mongol Empire | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| [quantify][citation needed] | |

| Template:Country data Inner mongolia: Naiman Banner[2] | [quantify][citation needed] |

| 940.000[4] | |

| Languages | |

| Mongolic,[5][6][7] Mongolic[8] | |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox (Mongolia) Protestantism (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan) Shamanism Nestorianism (Former)[citation needed] | |

The Naiman (/ˈnaɪmən/; Mongolian: ᠨᠠᠶᠢᠮᠠᠨ [ˈnɛːmɴ̩]; Kazakh and Kyrgyz: Найман [nɑjˈmɑn]), meaning The Eight, were a medieval tribe originating in the territory of modern Western Mongolia[9] (possibly during the time of the Uyghur Khaganate),[10] and are one of the 92 tribes of Uzbeks, modern Mongols[2] and in the middle juz of the Kazakhs.

History

[edit]In The Secret History of the Mongols, the Naiman subtribe the "Güchügüd" are mentioned. According to Russian Turkologist Nikolai Aristov's view, the Naiman Khanate's western border reached the Irtysh River and its eastern border reached the Mongolian Tamir River. The Altai Mountains and southern Altai Republic were part of the Naiman Khanate.[11] They had diplomatic relations with the Kara-Khitans, and were subservient to them until 1175.[12] In the Russian and Soviet historiography of Central Asia they were traditionally ranked among the Mongol-speaking tribes.[13] For instance, such Russian orientalists as Vasily Bartold,[9] Grigory Potanin, Boris Vladimirtsov, Ilya Petrushevsky, Nicholas Poppe,[13] Lev Gumilyov,[14] Vadim Trepavlov classified them as one of Mongol tribes.[13] Other scholars classified them as a Turkic people from Sekiz Oghuz (means "Eight Oghuz" in Turkic).[15][16][17][18] However, the term "Naiman" has Mongolian origin meaning "eight", but their titles are Turkic, and they are thought by some to be possibly Mongolized Turks.[19] They have been described as Turkic-speaking,[19] as well as Mongolian-speaking.[20] Like the Khitans and the Uyghurs, many of them were Nestorian Christians or Buddhists.

The Naimans were located to the west of the Mongols, and there were more Naimans than Mongols in the late 12th century. In 1199, Temüjin (Genghis Khan) together with an ally Ong khan launched a campaign against the Naimans.[21] They defeated Buyirugh, a Naiman khan who ruled the mountain lineage. In 1203, the last Tayang khan, the ruler of Naimans of the steppe, was killed after a battle with Genghis Khan. His son Kuchlug with his remaining Naiman troops then fled to the Kara-Khitan Khanate. Kuchlug was well received there and the Khitan Khan gave him his daughter in marriage. Kuchlug soon began plotting against his new father-in-law, and after he usurped the throne, he began to persecute Muslims in the Hami Oases. But his action was opposed by local people and he was later defeated by the Mongols under Jebe.

Although the Naiman Khanlig was crushed by the Mongols, they were seen in every part of the Mongol Empire. Ogedei's great khatun ("queen") Töregene might have been from this tribe. Hulegu had a Naiman general, Ketbuqa, who died in the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260.

After the collapse of the Yuan dynasty, the Naiman were eventually assimilated into Mongol, Tatar, and Kazakh tribes.[22]

Ethnic roots

[edit]According to Lee & Kuang, the Naiman and the Önggüt tribes were descending from the remainders of Turkic peoples of Central and Eastern Mongolia, which stood not in contact with Iranian groups West of the Altai Mountains, unlike "Western Turks". They were loosely controlled by the Khitan Liao and Jurchen.[23]

Other scholars connected them with Sekiz Oghuz.[24][25]

According to such orientalists as Vasily Bartold,[9] Grigory Potanin, Boris Vladimirtsov, Ilya Petrushevsky, Nicholas Poppe,[13] Lev Gumilyov,[14] Vadim Trepavlov[13] the origin of the Naimans was connected with the Mongol-speaking peoples. Gumilev believed that they were part of the Khitans.[14]

Among Mongols

[edit]The modern Naiman tribe is an ethnic group in Naiman Banner, Inner Mongolia of China. The clan Naiman changed the clan name and mixed with other tribes in Mongolia.[26]

Among Turkic peoples

[edit]Kazakhs

[edit]

Modern Kazakh historians claim that more than 2 million of the Kazakh population are Naimans (see Modern Kazakh tribes or Middle Juz). They originate from eastern Kazakhstan. Some Naimans dissimilated with the Kyrgyz and Uzbek ethnicities and are still found among them. Now, the Naimans are one of the big tribes of modern Kazakh peoples, they belong to Middle Juz of Kazakhs, live mainly in the eastern, central and southern parts of Kazakhstan, with a population of approximately one million among Kazakhs in Kazakhstan.

They also exist with considerable population among the Kazakhs in China, Uzbekistan and Russia, the Naiman tribe populations in the Kazakhs in China is 700000 or more, mostly living in the western part of Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region of China, in the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture. Naimans are also one of the major tribe among Kazakhs in the Uzbekistan, they also exist among Kazakhs in Kyrgyzstan and Russia.[28]

Hazaras

[edit]There is a tribe of Sheikh Ali Hazaras who are of Naiman origin. In Afghanistan they mainly reside in the Sheikh Ali District of the Parwan Province.[29]

Religion

[edit]The main religion of the Naimans was shamanism and Nestorian Christianity. The Naimans that adopted Nestorianism probably converted around the same time the Keraites adopted the religion in the 11th century.[22] They remained so after the Mongol conquest and were among the second wave of Christians to enter China with Kublai Khan.[30] Some Nestorian Naiman fled to Kara Khitai during the Mongol conquests where some converted to Buddhism.[22]

There was a tradition that the Naimans and their Christian relatives, the Keraites, descended from the Biblical Magi.[31] The commander of the Mongol army that invaded Syria in 1259, Kitbuqa, was a Naiman: he is recorded to have "loved and honoured the Christians, because he was of the lineage of the Three Kings of Orient who came to Bethlehem to adore the nativity of Our Lord".[32] However, Kitbuqa was slain and his army decisively defeated at the Battle of Ain Jalut, ensuring continued Muslim hegemony over the Levant.

Nestorianism declined and vanished among the Naiman soon after the collapse of the Yuan dynasty. Mongolian Naimans converted to Tibetan Buddhism in the sixteenth century. The Naiman assimilated into other ethnic groups living in Eurasia and likely adopted the religion and culture of the dominant group.[22] The Naimans who settled in the western khanates of the Mongol Empire all eventually converted to Islam.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Үндэсний Статистикийн Хороо. Найман.

- ^ a b c Очир А. Монгольские этнонимы: вопросы происхождения и этнического состава монгольских народов / д.и.н. Э. П. Бакаева, д.и.н. К. В. Орлова. — Элиста: КИГИ РАН, 2016. — 286 с. — С. 116—119. — ISBN 978-5-903833-93-1.

- ^ D. Kassymova, Z. Kundakbayeva, U. Markus. Historical Dictionary of Kazakhstan. — Scarecrow Press, 2012. — 362 p. — P. 191. — ISBN 978-0-8108-7983-6.

- ^ Казахов посчитали по родам: самые многочисленные — аргыны и дулаты https://365info.kz/2016/08/kazahov-poschitali-po-rodam-samye-mnogochislennye-argyny-i-dulaty

- ^ Man, John (2013). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. St. Martin's Publishing Group. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-1-4668-6156-5.

- ^ Rossabi, Morris (2012). The Mongols: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-993935-0.

- ^ Mote, Frederick W. (2003). Imperial China 900-1800. Harvard University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- ^ Тодаева Б. Х. (1985). Язык монголов Внутренней Монголии. Очерк диалектов. Москва: Наука. p. 84.

- ^ a b c Бартольд В. В. (1968). Сочинения. Том V. Работы по истории и филологии тюркских и монгольских народов. Москва: Наука. p. 104.

- ^ Кузембайулы А., Абиль Е. А. (2006). История Казахстана. Костанай: Костанайский региональный институт исторических исследований. p. 59. ISBN 978-9965-612-06-0.

- ^ History of Mongolia, Volume II, 2003

- ^ Michael Biran. The Empire of the Kara Khitai in Eurasian History,2005, page 57.

- ^ a b c d e Этнический национализм и государственное строительство. Москва: Институт Востоковедения РАН. 2001. p. 326. ISBN 978-5-89282-193-3.

- ^ a b c Гумилёв Л. Н. В поисках вымышленного царства. Трилистник птичьего полёта. 6. Прообраз героя легенды (1100≈1143) [окончание].

- ^ Ratchnevsky, Paul. "Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy". 2000, pp.1–4.

- ^ Roemer, Hans Robert; Scharlipp, Wolfgang-Ekkehard (2000). History of the Turkic Peoples in the Pre-Islamic Period. Klaus Schwarz Verlag. ISBN 3-87997-283-4.

- ^ Czaplicka, Marie Antoinette (2001). The Turks of Central Asia in History and at the Present Day. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4021-6332-6.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1987). A History of the Crusades. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-34770-9.

- ^ a b Li Tang (29 May 2009). "Medieval Sources on the Naiman Christians and their Prince Küchlüg Khan". In Dietmar W. Winkler; Li Tang (eds.). Hidden Treasures and Intercultural Encounters. 2. Auflage: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. Lit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-643-50045-8.

- ^ Barbara A. West, ed. (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Chelsea House Publishers. p. 577. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- ^ Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank, eds. (26 January 1995). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368: Alien Regimes and Border States, 710 -1368 v. 6. Cambridge University Press. pp. 338–339. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- ^ a b c d Tang, Li (2011). East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China. Harrassowitz. pp. 30–32. ISBN 978-3-447-06580-1.

- ^ Lee, Joo-Yup; Kuang, Shuntu (2017-10-18). "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and y-dna Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples". Inner Asia. 19 (2): 197–239. doi:10.1163/22105018-12340089. ISSN 2210-5018.

The Turkic tribes that were still present in the Mongolian steppes at the turn of the thirteenth century included the Önggüt and the Naiman. The Önggüt were probably descended from the Chuyue, the above-mentioned Western Tujue tribe. The Yuanshi states that the chief of the Önggüt, Alawusi Tijihuli (阿剌兀思剔吉忽裏), who submitted to Chinggis Khan in 1203, was 'a descendant of the Shatuo-yanmen (沙陀雁門之後)' (Yuanshi 118.2923). In turn, the Xin Tangshu relates that the Shatuo (沙陀) were 'a progeny of the Chuyue, a separate tribe of the Western Tujue (西突厥別部處月種也)' (ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn ʿAṭā Malik Juvaynī 1958: vol. 1, 55–6).28 The origin of the Naiman is not well documented. However, one may speculate that the Naiman were an offshoot of the Uighurs. As to the physiognomy of the Önggüt and the Naiman, Rashīd al-Dīn relates that the former 'resembled the Mongols (bi-mughūl mānand)' (Rashīd al-Dīn Fażlallāh Hamadānī 1988: Vol. 1, 99; Rashiduddin Fazlullah 1998–99: Vol. 1, 70) and that the girls (dukhtarān) of the latter were 'renowned for their beauty and comeliness (bi-ḥusn va jamāl mashhūr bāshand)' (Rashīd al-Dīn Fażlallāh Hamadānī 1988: Vol. 1, 99; Rashiduddin Fazlullah 1998–99: Vol. 1, 70).

- ^ Ratchnevsky, Paul. "Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy". 2000, pp.1–4.

- ^ Roemer, Hans Robert; Scharlipp, Wolfgang-Ekkehard (2000). History of the Turkic Peoples in the Pre-Islamic Period. Klaus Schwarz Verlag. ISBN 3-87997-283-4.

- ^ The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, by René Grousset, p190

- ^ Муканов М. С., Этническая территория казахов в 18 – нач. 20 вв ("Ethnic territory of Kazakhs from the 18th to the beginning of the 20th century"), Almaty, 1991.

- ^ "Kazakh shezhire"

- ^ Hazara tribal structure, Program for Culture and Conflict Studies, US Naval Postgraduate School

- ^ Cary-Elwes, Columba. China and the Cross. (New York: P. J. Kennedy and Sons, 1956) p. 37

- ^ In regno Tarsae sunt tres prouinciae, quarum dominatores se reges faciunt appellari. Homines illius patriae nominant Iogour. Semper idola coluerunt, et adhuc colunt omnes, praeter decem cognationes illorum regum, qui per demonstrationem stellae uenerunt adorare natiuitatem in Bethlehem Judae. Et adhuc multi magni et nobiles inueniunt inter Tartaros de cognatione illa, qui tenent firmiter fidem Christi. (In the kingdom of Tarsis there are three provinces, whose rulers have called themselves kings. the men of that country are called Uighours. They always worshipped idols, and they all still worship them, except ten families of those Kings who through the appearance of the Star came to adore the Nativity in Bethlehem of Judah. And there are still many of the great and noble of that family found among the Tartars who hold firmly to the faith of Christ.) De Tartaris Liber,, 1307 AD, also called La flor des estoires de la terre d'Orient, by Hayton of Corycus in Novus orbis regionum ac insularum veteribus incognitarum, edited by Simon Grynaeus and Johannes Huttichius, Basel, 1532, caput ii, De Regno Tarsae, p.420. English translation.

- ^ Hayton of Corycus, La flor des estoires de la terre d'Orient (1307), quoted in Ugo Monneret de Villard, Le Leggende orientali sui Magi evangelici, Citta del Vaticano, Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, 1952, p.162. Also found in De Tartaris Liber, caput XXX, De Cobila Can quinto Imperatore Tartarorum , on page 445: "Nam ipse [Guiboga] fuerat de progenie trium regum, qui uenerunt natiuitatem domini adorare" ("For he was a descendant of the Three Kings who came to the Nativity to adore the Lord").